Memorial Day events honor fallen soldiers, women’s suffrage, and freedom from slavery

June 5, 2021 | By Tulley Hescock | Community News Service

‘Salute the Dead’

By Tonya West

Rain drops on us rusty singers

Led by a vision in purple:

A soprano in a flower-rimmed bonnet

Mashes up a suffrage song with “Glory Glory”

The mic crackles, “And now for the salute”

Rifles cocked, hands snap to brows

One fistful of Dame’s Rocket is raised

Then three rounds, each preceded by the call:

“Salute the dead! Salute the dead! Salute the dead!”

Alarmed, birds fly out from the trees and vanish.

~ Hope Cemetery, Waterbury, May 31, 2021

Tonya West lives in Waterbury and submitted this poem inspired by the Memorial Day ceremony.

Waterbury’s Memorial Day ceremony was one of the first public events this year as the COVID-19 pandemic eases and it managed to cover several poignant themes.

Hosted by the Waterbury Historical Society and the American Legion Post 59, the Monday morning ceremony and program honored fallen U.S. service members, marked last year's centennial of the 19th Amendment, and shared stories of several lesser-known local historical figures.

More than 50 people gathered at the entrance to Hope Cemetery in honor of Memorial Day and many stayed past the American Legion’s ceremony to partake in the annual Ghost Walk hosted by the historical society.

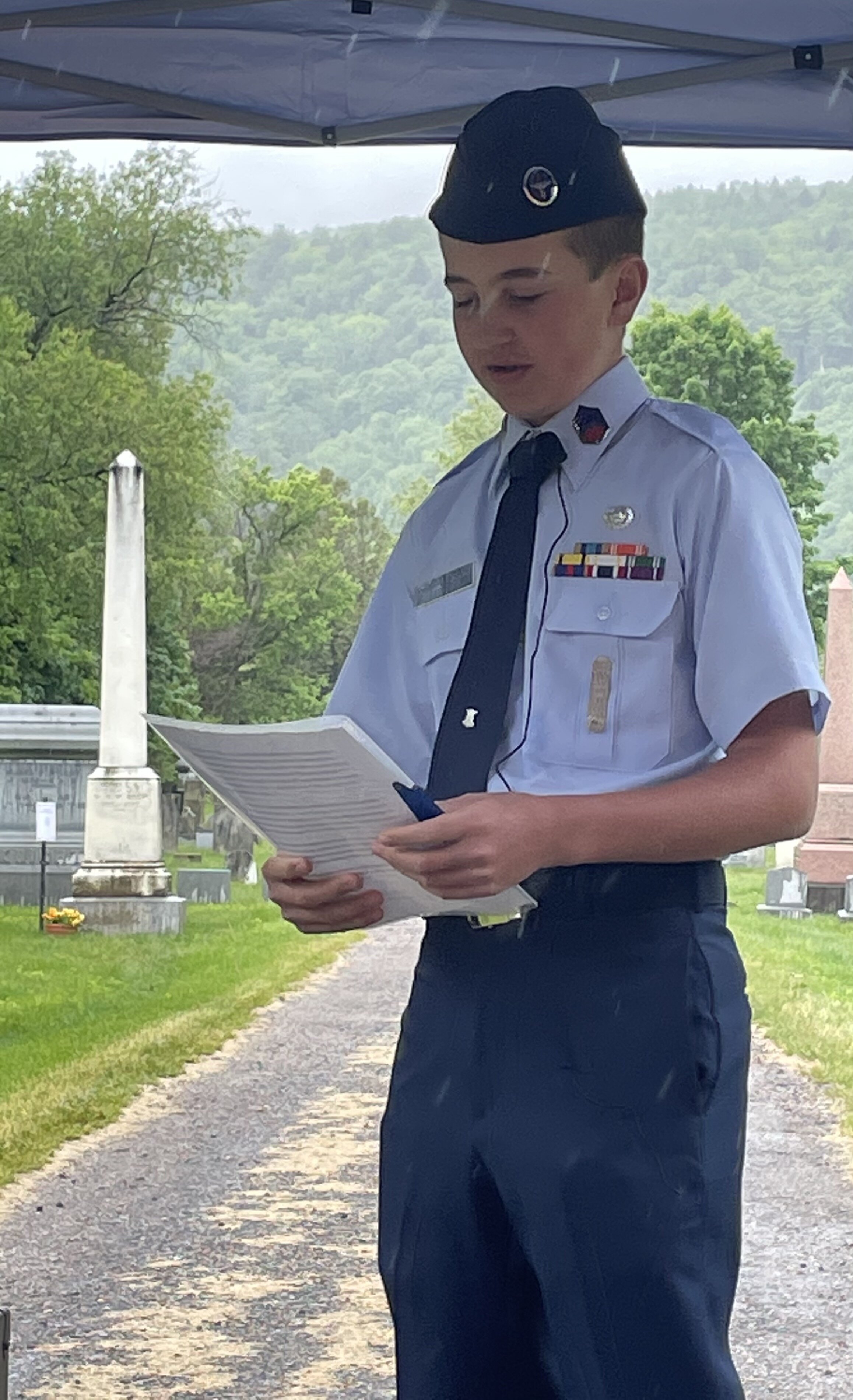

The American Legion’s Color Guard and Firing Squad paid tribute to those who served and died in military service. The program also included remarks from Crossett Brook Middle School eighth grader Nate Conyers, a member of the Civil Air Patrol Cadet Section. He shared why he believes it is important to serve the nation and said he one day hopes to serve by joining the U.S. Air Force.

Conyers challenged listeners to “step up and serve our nation by starting in our community. Starting with the small things is the best way to improve the lives of everyone in the United States,” he said. “If everyone in this country did one small act of kindness each day toward their neighbor, that is 330 million examples of improving the well-being of everyone in our homeland.”

Vermont folk singer and historian Linda Radtke attended to sing a rendition of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic (Glory Glory Hallelujah)” with lyrics about the suffrage movement turning it into a song that speaks to women’s equality and strength. Radtke delivered her performance wearing a bright purple period gown and hat.

The legion’s ceremony ended with “Taps” played by a lone bugler and the four-member firing squad sending off a three-round volley to honor the dead.

Ghost Walk brings history to life

Next, the program shifted to the Ghost Walk, an annual event by the historical society that highlights the stories of various figures in the town’s past. Group members led visitors through a tour of Hope Cemetery sharing the stories of those buried. This year the theme of the walk was “breaking-boundaries'' as it focused on three significant individuals: two 19th-century Black men who were freed slaves, and a woman who ran Waterbury’s Green Mountain Seminary school and became a women’s suffrage leader in Vermont the early 20th century.

In light of the Black Lives Matter movement of the past year and gender equality conversations, Waterbury Historical Society President Cheryl Casey said that event organizers focused on diversity for this year’s Ghost Walk.

“We really wanted to highlight the perhaps lesser-known, but significant boundary-breaking citizens of our past,” Casey said.

Charles Daggs' headstone in Hope Cemetery notes he was 'A Freedman.' Photo by Lisa Scagliotti.

Historical society speakers established three stations for storytelling – each at a gravesite significant to the figure they planned to discuss.

Waterbury resident David Luce shared the story of Charles Daggs, a freed slave who came to Waterbury from Virginia to live with the Dillingham family during the Civil War. Paul Dillingham was lieutenant governor during the Civil War and later served as governor of Vermont. His son, Charles, served in the Union Army.

Upon settling in Waterbury, Daggs attended Waterbury High School where he was considered a top student. “They said his performance was superior to any other scholar in the school in Waterbury,” Luce said.

Daggs lived with the Dillinghams for three years before he died at the age of 23 from an illness. The Dillinghams made sure he was buried in Hope Cemetery where their family is buried – a graveyard that had previously only interred white residents. His gravestone from 1864 bears the inscription “A Freedman.”

Some question remains as to the actual location of Daggs’ grave with some historical accounts saying it was in the Dillingham family plot but cemetery records showing it was in a different section of the cemetery.

Waterbury offered a fresh start

Lifelong Waterbury resident and avid local historian Skip Flanders did much of the research on Daggs as well as the background of Lorenzo Bryant and his descendants. Flanders told Bryant’s family story in the center of the cemetery beside a row of gravestones.

Bryant was the other freed slave who, at age 20 like Daggs, accompanied Charles Dillingham and First Lt. William W. Henry to Waterbury in 1861. Bryant was born in Fairfax County, Virginia. He married a Waterbury widow, Eliza Wood, whose husband had died in the war. In 1873, Bryant, who worked as a carpenter, purchased a lot on North Main Street where he built a house for his family and the building remains there today. He was laid to rest in Hope Cemetery in a grave marked “Father” that Flanders labeled for the talk.

This undated photo is believed to be Celia Bryant, daughter of Lorenzo Bryant, in a wedding dress. Photo courtesy Waterbury Historical Society

Flanders said he felt it was important to share both of these men’s stories. “They were former slaves, came to Waterbury, and contributed to life in Waterbury. [Bryant’s] obituary said he was a respected citizen,” Flanders said.

Flanders' research followed Bryant’s family into the 1940s with the story seeming to end with the death of Bryant’s daughter, Celia, in Ohio. Flanders said he believes an undated photograph in the Waterbury Historical Society archives of a young Black woman in a wedding dress is Bryant’s daughter at the time of her first of three marriages. She eventually died in 1947 and reportedly is buried in an unmarked grave in Ohio. Flanders said he hopes to continue his research on Bryant’s descendants to share during a future Black History Month.

Historical society member Jan Gendreau said there were very few people of color in Vermont during the 1860s and even fewer in Waterbury, making these two men – Daggs and Bryant – stand out as “breaking-boundaries” in their historical moment.

Attendees at the historical walk took turns listening to the stories at each of the three stations. Roger and Pam Clapp said they joined the event for the first time and appreciated the focus on the two Black residents.

“The grave sites served to provide a physical link of their presence in Waterbury to those of us gathered around to listen to their stories and connections with families still living in town,” Roger said. Pam Clapp carried wild phlox she picked at the edge of the cemetery and placed some at each of the graves.

Women signed on for voting rights

Casey chose the gravesite of two of the women – Hannah French Merriam and her daughter Rebecca Merriam Forrest – to deliver her presentation that highlighted the suffrage movement through the story of Elizabeth Colley.

According to Casey, Colley was an “educator, business owner and leader” who pushed for women’s right to vote and advocated for the temperance movement. “The suffrage movement in Vermont can be traced back to 1870, and there are eight women buried here in Hope Cemetery who are among the signers of a petition to the Vermont legislature in 1870 for the right to vote,” Casey said. Those gravesites were marked on Monday with flowers and small signs.

It wasn’t until 50 years later on February 8, 1921 that the legislature ratified the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that allowed women to vote. Colley is not buried in Waterbury; her grave is in Franklin, New Hampshire, at a family plot.

Casey said she was excited to share Colley’s story at the event and said she resonated with her. “I was really taken by her courage and independence in living her life and doing her own thing. I thought she was especially extraordinary for her commitment to education,” Casey said.

Waterbury resident Kerry Hurd said he has been coming to the Ghost Walk for years and enjoys learning local history. “I’ve gone through this cemetery several times, but it's so cool actually getting to meet some of the people that are here,” Hurd said.

The women's suffrage movement in 1912 is strong as local women march toward Bank Hill on South Main Street in the Waterbury Fourth of July parade. Waterbury Historical Society photo.

Community News Service is a collaboration with the University of Vermont’s Reporting & Documentary Storytelling program.

Written versions of the Ghost Walk presentations are posted in the Community section of Waterbury Roundabout.