Closing Time: How (some) turtles shut their shells

October 30, 2024 | By Jenna O’del | The Outside Story Illustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol

In cartoons, when a turtle is spooked, it retreats into and closes up its shell. While used for comic effect, this imagery is based in fact – although not all turtles are capable of this protective feat.

In the Northeast, there are three native turtle species that have hinged shells: the Blanding’s turtle (Emydoidea blandingii), the common musk turtle (Sternotherus odoratus), and the eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina).

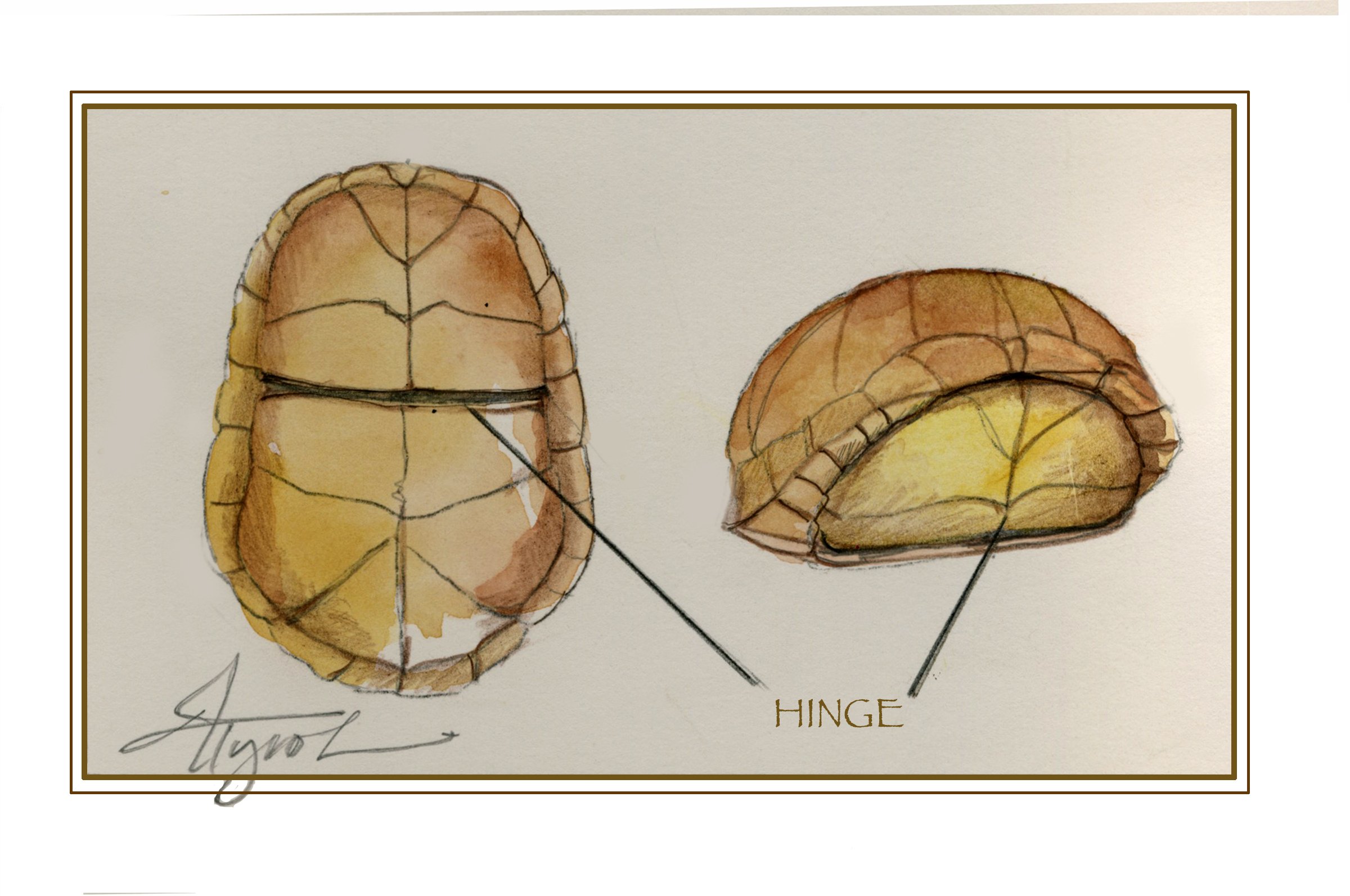

Turtles have a lower shell, called a plastron, and an upper shell, or carapace. In hard-shelled turtle species, the shells are made up of bony plates that are covered with scale-like “scutes” which are made of keratin, the same protein found in our fingernails and hair, and give turtle shells their color.

Hinged-shell turtles have a split in the plastron, just behind the turtle’s front legs. The plates along this hinge are connected by cartilage, and specialized joints allow these turtles to pull the plastron toward the carapace; some hinged-shell species can completely close their shells, while others can only partially close.

While most turtles can retract their heads and limbs into their shells, being able to seal these body parts within is an effective defense against predation. Several animals, from coyotes to otters, will eat turtles. “If you’re a fairly adept critter like a raccoon, you can pry out a leg and have a snack,” said Jim Andrews, coordinator of the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas. “It’s not at all unusual for us to find wood turtles or painted turtles with missing legs.”

Hinged-shell turtles, however, particularly eastern box turtles, are well protected. Flexing its hinge joint, a box turtle can completely close its plastron against its high-domed, yellow-patterned carapace. Blanding’s turtles can close their yellow-spotted black shells most of the way, so raccoons and otters, their most common predators, can’t make them into an easy meal. However, there are slight gaps between the Blanding’s plastron and carapace.

Licensed wildlife rehabilitator Dallas Huggins of New Hampshire Turtle Rescue said that while many of the turtle species they rescue have lost limbs to predators, that is rarely the case with box turtles and Blanding’s turtles. In fact, these hinged-shell species are so good at protecting themselves that it poses a rehabilitation challenge. “They have a lot of strength in that [hinge],” Huggins said, noting that wildlife rehabilitators often have to prop the shells open with corks “to keep them from shutting on your finger during a procedure.”

Musk turtles have the slightest hinge of all, said Andrews, adding “I’ve never seen them use it.” Andrews said the musk turtle hinge may be vestigial, a remnant of evolutionary history. After all, these turtles have another form of defense: they smell. Also known as stinkpots, these small, dark brown turtles release musky fluid when threatened. The odor discourages predators, although everything from snakes to minks still eat the little stinkers. Blanding’s and musk turtles can also slip into their wetland homes to swim away from danger. Box turtles, on the other hand, “are entirely terrestrial,” Andrews said, preferring open areas such as shrublands and fields. “They’re out and they’re exposed.”

However, even hinged shells do not protect these species from other dangers. Blanding’s and eastern box turtles are listed as species of concern in New Hampshire, and musk turtles have the same status in Vermont. Wildlife biologists blame much of the decline of these and other turtle species on habitat loss and road fatalities, as turtles often cross roads to reach egg-laying areas. All three of our region’s hinged-shell turtles have also been subject to the illegal pet trade. In June, a woman was caught attempting to smuggle 29 box turtles into Canada by carrying them via kayak across Lake Wallace, which spans the Vermont-Canadian border.

Like other northeastern turtles in autumn, these species are preparing to brumate, which means their metabolism will slow down and they’ll become sluggish, entering a state of torpor that may last until spring. Blanding’s and musk turtles usually overwinter at least partially buried under mud and leaves on the bottoms of ponds and sluggish streams, while box turtles usually find a sandy spot on land and dig down under the leaf litter to settle in for the winter.

Come springtime, these and other turtle species will emerge and head back to their nesting grounds, facing dangers from cars to predators.

Jenna O’del is a biologist and science writer based in Rhode Island. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.