Northeastern hawks soar through winter

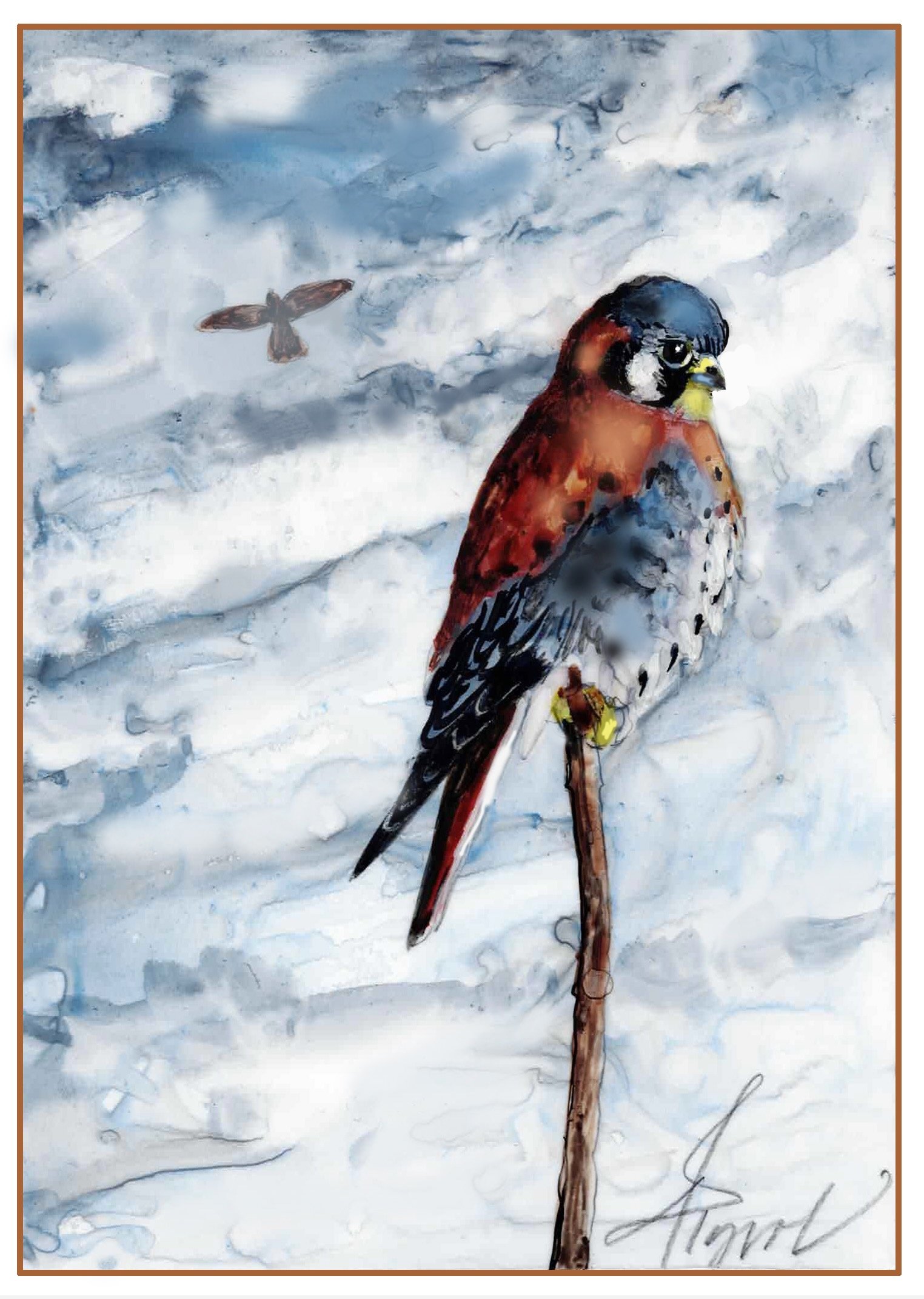

January 31, 2025 | By Susan Shea | The Outside StoryIllustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol

Driving on Vermont’s Interstate highways in winter, I often notice large hawks perched in trees on woodland edges at regular intervals along the road. With the stark landscape providing better visibility and many bird species gone for the winter, this is a great time of year to hawk-watch.

The raptor I see most along the highway has a white breast with a band of dark brown streaks across the belly, a brown back, and a reddish tail. This is a red-tailed hawk, North America’s most common hawk.

Some species of hawks that breed in northern New England migrate south for the winter, but most red-tailed hawks remain and are joined by others of their kind from Canada. I frequently see red-tailed hawks soaring above open areas. They turn slow circles on broad, rounded wings, with their tail feathers fanned out, and occasionally emit a piercing kreer. Red-tailed hawks belong to the genus Buteo, and are often referred to simply as buteos; all hawks in this group share this distinctive flight silhouette.

From the sky, they scan for prey with their keen eyesight until they spot an unsuspecting rodent, then suddenly swoop down to grab it in their talons. They also hunt from high perches, such as trees along highways. These raptors prey on mice, voles, rabbits, squirrels, and some waterfowl and other birds. They prefer open country interspersed with woods. In winter, the Champlain Valley and parts of the Connecticut River Valley are hotspots for them.

Another hawk that can be spotted in open areas is the American kestrel, North America’s smallest falcon. Males have a rusty back and tail, a slate-blue head and wings, and the pointed wings and long tail of a falcon, while females are just rufous. Look for a small hawk perched on a utility pole or wire or hovering over a field, flapping its wings.

In summer, kestrels consume many grasshoppers and other insects, but in winter they prey solely on small rodents and birds. They will stash surplus kills in shrubs and tree hollows for future meals. Kestrels favor open areas such as fields, pastures, and parks. They are common in the Champlain Valley in winter.

Kestrel populations have decreased 53% over the last fifty years, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey. Declines are likely due to the cutting of dead trees they use for nesting, the loss of insect prey due to pesticides, and farming practices that remove trees and brush, making rodents scarce.

Some hawk species hunt other birds and will visit feeders in winter, hoping to catch a tasty meal. One is the sharp-shinned hawk, our smallest accipiter. Raptors in this genus have short, broad wings and long tails which enable them to fly through the woods at high speeds in pursuit of prey. Adult sharp-shinned hawks have a gray back, orange, horizontal bars across the breast, and a banded tail. Although they breed in dense forests, in winter they frequent woodland edges, fields, and suburban backyards with feeders where it’s easier to spot songbirds and mice.

The Cooper’s hawk, a medium-sized accipiter, also visits bird feeders in winter. Very similar in appearance to the sharp-shinned hawk, it can take on larger prey such as pigeons, doves and squirrels.

While snowshoeing or skiing in the forest, if you’re lucky you may glimpse an American goshawk, our largest accipiter. This uncommon and secretive bird of prey has a gray back, streaked breast, and a white stripe over its orange eyes. The goshawk hunts larger prey than our two other accipiters, such as rabbits and grouse. In summer, goshawks are known to fiercely defend their nests. With the mate making a racket nearby, I was once dive-bombed by a goshawk when I unwittingly got too close to a nest while hiking.

In some winters, it’s possible to see an arctic hawk called the rough-legged hawk in northern New England. Another species of buteo, these hawks move south seeking open habitat similar to the northern tundra such as farm fields and airports. This raptor has narrow wings, a long tail, and a large head. The dense feathering on its legs, an adaptation to cold, gives the rough-legged its name. The plumage of this species varies in pattern and color.

While driving, gazing at your backyard feeder, or walking outdoors this winter, keep your eyes peeled for these skilled hunters and masters of flight.

Susan Shea is a naturalist, writer, and conservationist based in Vermont. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.