The Outside Story: The rare and reclusive spotted turtle

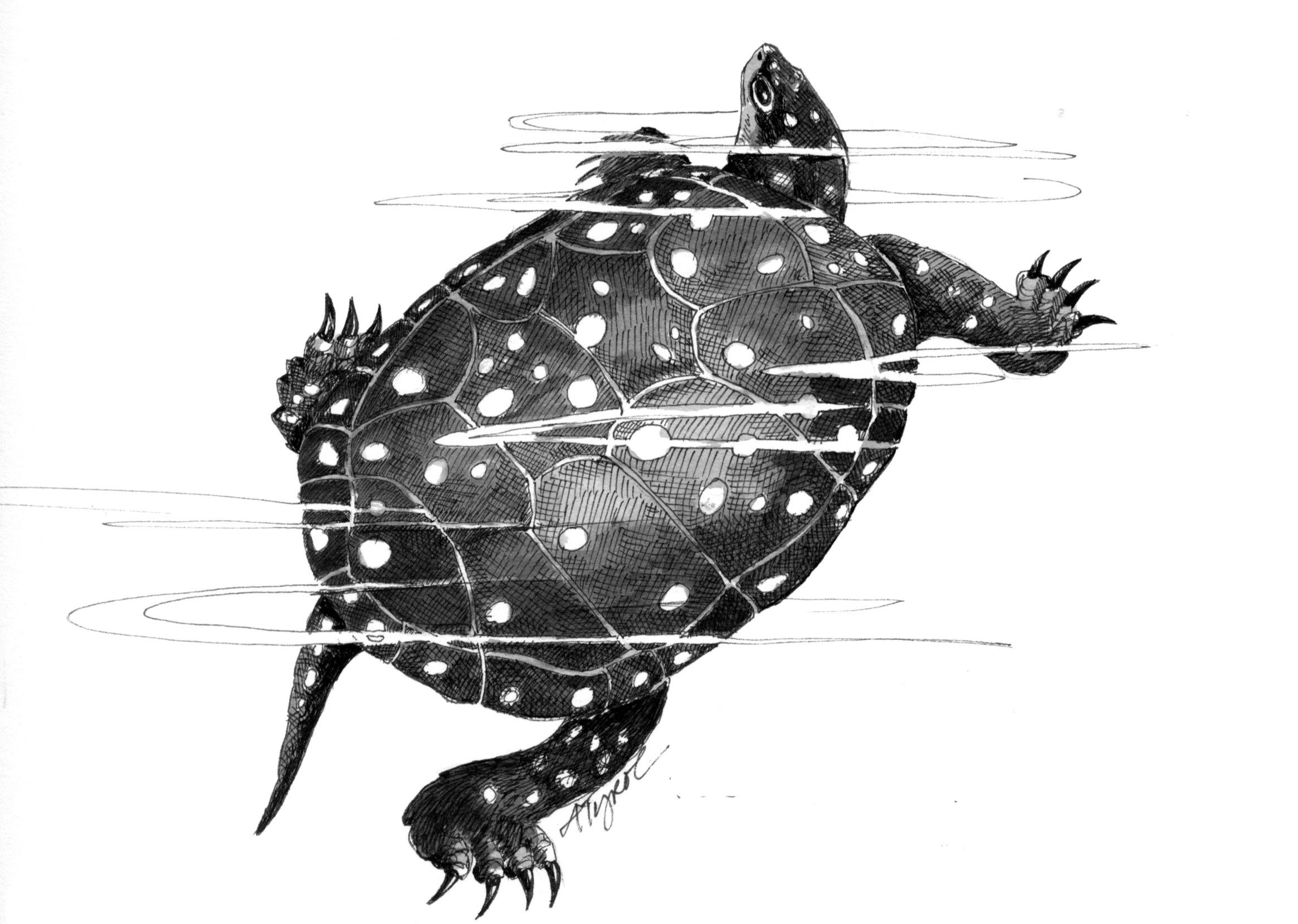

July 25, 2023 | By Susan SheaIllustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol

Named for their polka-dot-like markings, spotted turtles have declined throughout most of their range, which stretches from Maine south along the Atlantic coastal plain to northern Florida, and from western New York into the eastern Great Lakes states. This species is listed as threatened or endangered in northern New England states.

While I have never seen a spotted turtle in the wild, I had the chance to see one years ago at the Connecticut nature center where I worked. This turtle was about 4 inches long, with a smooth, black carapace sprinkled with yellow dots. The skin on its head, neck, and legs was marked with tiny yellow speckles. The turtle’s underside, or plastron, was yellow-orange with large black blotches along the edges.

These turtles are semi-aquatic, spending time on both land and water. They travel among a mosaic of wetland types, including ponds, swamps, vernal pools, fens, and slow-moving sections of small rivers, foraging there and in woodlands and meadows along their route.

Spotted turtles emerge from hibernation before other turtle species in our region. They begin swimming as early as late March, when there may still be ice on their wintering ponds. In early spring, they bask on logs, rocks, or shores, soaking up heat from the sun. They also breed at this time. After mating, spotted turtles often move to woodland vernal pools, where they feast on amphibian eggs and tadpoles. In other wetlands, they feed on aquatic insects, small fish, crayfish, and plants.

In June, females travel to open, sandy or gravelly areas to lay their eggs. A spotted turtle will dig a shallow, flask-shaped nest about 2 inches deep and deposit two to five ovoid eggs, then fill in the nest and smooth it over. The eggs will hatch in September, and the round, 1-inch, unspotted hatchlings will head for wetland edges to forage.

During summer heat spells, spotted turtles may become dormant for days or weeks, estivating in a dug depression in the ground, in moist hummocks of vegetation, or inside muskrat houses. In September, these turtles travel to hibernation sites on pond bottoms, in underwater rock caves, or in hummocks. Activity decreases and they enter winter dormancy in October, sometimes in communal groups.

The spotted turtle is listed as endangered in Vermont, where there are only three known populations, all in the southern half of the state. In New Hampshire, where this turtle is a threatened species, it is found mainly in the southeastern corner. In Maine, where the species is also threatened, spotted turtles occur along the southern coast. In southern New England and New York, this reptile is considered a species of special concern.

Spotted turtles may travel up to three-quarters of a mile on their annual journeys. According to herpetologist Jim Andrews, coordinator of the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas, the species’ nomadic lifestyle and use of upland as well as wetland habitats make it particularly vulnerable to habitat fragmentation and road mortality. The illegal collection of turtles for the pet trade has also contributed to population decline. Because these turtles don’t reach sexual maturity for eight to ten years and have a low reproductive rate, removing even a few turtles can wipe out a population.

Fish and wildlife agencies in northern New England monitor spotted turtle populations. In many places, they have erected turtle crossing road signs, installed turtle tunnels beneath roads, and modified railroad tracks so the animals don’t get stuck while crossing. The conservation of large, intact wetland complexes and their surrounding landscape is critical to the survival of these turtles, said Andrews.

Spotted turtles tend to hide underwater and in vegetation, making it difficult to find new populations. A new environmental DNA study, a collaboration between the University of Vermont and Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, will collect water samples and analyze the DNA to detect whether this species occurs in particular waterbodies.

If you are lucky enough to see a turtle with yellow spots, please take a photo and report it to the Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas or to your state wildlife agency. Watch out for turtles crossing roads, and never remove a turtle from the wild.

Susan Shea is a naturalist, writer, and conservationist based in Vermont. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.