He told Vermonters’ stories, now Peter Miller is part of Vermont history

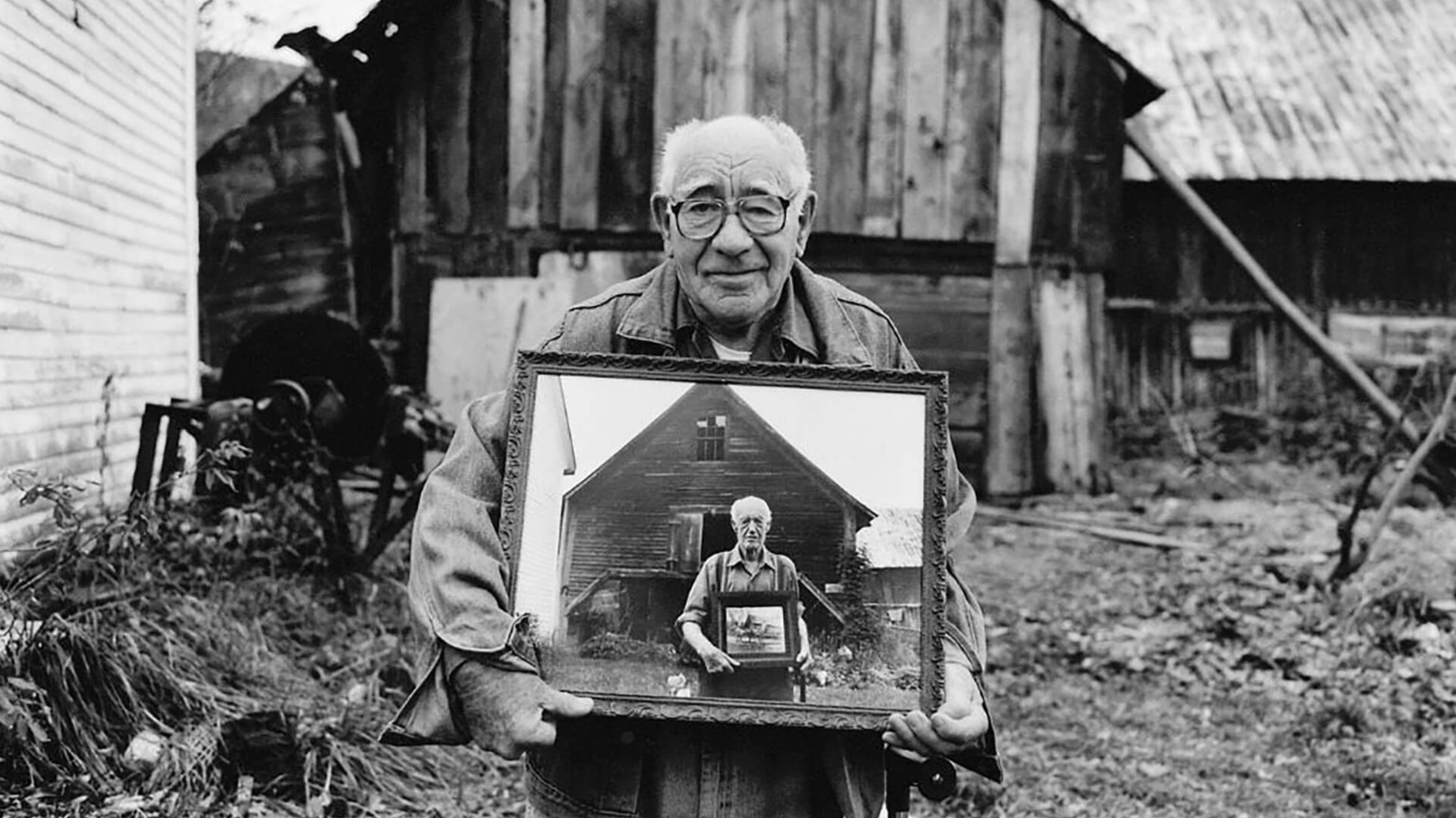

April 27, 2023 | By Cheryl Casey | Correspondent Peter Miller, 1934 - 2023. Photo by Gordon Miller (no relation)

Driven by a sense of urgency that the world was changing much faster than people could prepare for, photographer and writer Peter Miller dedicated nearly 70 years to capturing the landscapes, traditions, people, and communities of Vermont before it all faded from sight and mind. In his Waterbury gallery and in the pages of six of his books, the faces of generations of Vermonters stare back, their inner worlds coaxed forth by Miller’s camera and the nuances of his black-and-white medium.

On the pages, Miller dutifully documented his subjects’ stories, giving readers both visual and narrative slices of dozens of biographies over the years.

Last week, Miller’s storytelling days came to an end.

On Monday, April 17, Miller passed away at his residence in Stowe at the age of 89, his sister-in-law, Mary Miller, of Waterbury Center confirmed. “His health had been failing. He was in and out of the hospital,” she said.

Born in New York City on January 6, 1934, Miller’s future interweaving of two of his great loves – Vermont and photography – seemed fated when he moved to the Green Mountain State with his mother in 1947. Miller’s father, an alcoholic and Wall Street broker, had died during Miller’s senior year at Burr and Burton Academy, and his mother moved the family to what was then considered a very inexpensive state. After thieves made off with some of Miller’s guns, he used the subsequent insurance check to purchase a very different piece of equipment: a Kodak twin lens camera.

This sign marked Peter Miller's former home and gallery along the stretch of Vermont Route 100 known as Colbyville in Waterbury. The 1959 portrait of Weston hillside farmers Will and Rowena Austin is among Miller's earliest work documenting Vermonters. “They became part of the fabric of my life,” Miller told Yankee Magazine in 2012 of the Austins. Photo by Lisa Scagliotti

Miller’s studies at the University of Toronto led him to the tutelage of Yousuf Karsh, an Armenian-Canadian photographer revered for his portraiture. Traveling to Europe as Karsh’s assistant, Miller worked on photo shoots of famous figures like John Steinbeck, Albert Camus, Pope Pius XXIII, and Pablo Picasso. According to his biography on his website, Miller returned to Europe after joining the U.S. Army as a Signal Corps Photographer. Living in Paris for those two and a half years, Miller spent his free time honing his craft by photographing street scenes.

Having built his expertise in portraits, landscapes, and scenes of everyday life, Miller had one last crucial skill to master: writing. After his return from Paris, Miller accepted a position as a reporter-writer for LIFE magazine, a national weekly magazine noted, ironically, for the quality of its photography.

“I was not allowed to take photographs,” Miller explained in a 2017 video interview produced by the Vermont Ski & Snowboard Museum. “I was hired as a reporter…and that’s what I did. I learned how to write. The stress was incredible trying to put out a magazine every week,” he remembered.

The pressure of those deadlines soon took their toll, and Miller simply quit. “I got up to Vermont and I said, what have I done?...I don’t have any job, I left the best job in journalism in the world, what am I doing? It was a mess,” he laughed, adding, “The cameras are what saved me.”

So did the booming interest in skiing in the 1960s. Picking up assignments from Vermont Life and various ski magazines, Miller traveled the world photographing skiing’s greatest athletes and writing articles about the sport. Sometimes he didn’t have to travel far at all, such as when he covered the 1966 Internationals at Stowe.

Also down the road, in Richmond, the Cochran children were lighting up their parents’ ski slope as racers, and Miller’s initial photo essay for his Vermont Ski magazine turned into a record of the four siblings - Marilyn, Barbara, Bob, and Lindy - growing up as teenagers and competing for the U.S. Ski Team. All were national champions at least twice, and Barbara won Olympic gold in slalom in 1972.

“I seemed to be right at the cusp of a lot of things, and I don’t know why,” Miller told Vermont Ski & Snowboard in 2017. “Things were exploding…my luck, or whatever it is…I just learned a lot about [photography] in Vermont,” he said.

It was perhaps as he was perfecting his craft through close observations of the Vermont landscape that he began to see what others had not - an endangered way of life and a fast-morphing state answering the calls of gentrification, interstate highway travel, and new economic initiatives.

The realization led to his first book, a coffee-table collection entitled Vermont People (1990). Miller published the book with his own money and his own imprint, Silver Print Press, in a gesture of defiance toward the very titans of publishing whose for-profit paradigm he saw as contributing to Vermont’s fading way of life. In press releases about the book, Miller described himself as a “David fighting Goliath-sized publishers,” according to the “About” page on his website.

Peter Miller's portrait of 1998 U.S. Senate candidate Fred Tuttle is one of his best-selling photographs and posters. The image has been donated to the Waterbury Historical Society. Photo courtesy Peter Miller

Vermont People outsold all expectations and inspired five more Vermont-based books published by Silver Print Press: Vermont Farm Women (2002), Vermont Gathering Places (2005), Nothing Hardly Ever Happens in Colbyville, Vermont (2008), A Lifetime of Vermont People (2013), and Vanishing Vermonters: Loss of a Rural Culture (2017), as well as a revised edition of Vermont People in 2003.

Miller’s books struck home in the hearts of Vermonters. In a December 2015 blog post on his website, Miller summarized the letters and comments he received in response to A Lifetime of Vermont People: “[they] discuss their inability to cope financially and a rising anger about the legislature and the state government.”

The books’ appeal comes from their powerful combination of Miller’s images and the narratives he penned from time spent with his subjects both photographing and interviewing them. Willie Docto and Greg Trulson run Moose Meadow Lodge and Treehouse in Duxbury. They went from admiring Miller’s work to participating in one of his projects.

“The original ‘Vermont People’ book was one of the first things we bought when we moved to Waterbury in 1996. It is such a beautiful collection of Peter’s work,” Docto said. “Our guests really enjoy browsing through it. So, it was such an honor that Peter invited us to be included in his follow-up book, ‘A Lifetime of Vermont People.’

“Although we had known Peter for many years, he spent several hours interviewing us, really trying to get to know us deeper, before even photographing us,” he recalled. “It was important to him to include LGBTQ representation in his book, so we are humbled that we will forever be part of the Vermont story that Peter photographed.”

Peter Miller photographed dairy farmer Rosina Wallace with a portrait of her great-grandmother Lavina Wallace for his 2002 'Vermont Farm Women' book.

Waterbury farmer Rosina Wallace was among the subjects in Vermont Farm Women. "I felt like he was a cheerleader for me, and for Vermont," Wallace said. "He saw it as it used to be – the ruralness of Vermont and Vermonters."

That passion was unmistakable in Miller's photographs and writing, she continued. "Some of that is lost now that he's gone," she added.

Wallace found Miller to be laid-back and easy to work with, recalling the several occasions she worked with the prolific photographer. One time in the late 1990s, Wallace invited Miller to a picnic at the farm for youngsters in the Fresh Air program who were spending summertime in Vermont. Wallace hosted kids in the program for years.

Miller captured the energy of the afternoon and the spirit of the children, Wallace said, "the excitement, the anticipation, the kids in action playing all of the games."

Miller wasn't on assignment at the time, Wallace recalled. He shot the photos as a favor, giving her the prints and the film. Sadly, Wallace no longer has either today. “So much of that memorabilia I had was lost,” she said, referring to the April 1 fire in 2018 that devastated the family farm. The barns with 23 cows and calves inside along with the original farmhouse where Wallace's brother Kay Alan lived and Rosina's two-story modern wood frame home were destroyed.

Miller visited the farm the day after the fire. That was the last time he photographed Rosina and Kay Alan amidst the wreckage. He wrote about that day and posted images he made in that moment on his blog along with an excerpt from his "Vermont Farm Women" essay about Wallace years before:

“I saw and heard nothing the night of the fire but in the morning we all knew. I drove up the steep hill and headed north on Blush Hill where a road sign warned of crossing cattle. I turned into the driveway where the farm is—used to be. Now—devastation. A Cat excavator was compacting scorched and twisted metal into piles topped by a tractor upside down, its belly exposed, waiting for evisceration during this cruel month. Another tractor, a soot-black skeleton, was perched above another tangle of metal, holding its shape and dignity. My eyes swept over the detritus of this farm, nothing but ash and mud, warped metal and charcoal-skin barn beams. Tears ran down my cheeks.”

According to Wallace, Miller’s patience with his subjects only fed into his vision. “He knew exactly what he wanted the picture to be,” she said. “The color, the clothing, the time of day because of the light. He was very conscious of the background. But he was not bossy. He was professional.”

In his blog, Peter Miller posted this image of Rosina and Kay Alan “Wally” Wallace with the Wallace Farm's dog Bodhi, taken on April 2, 2018.

Sister-in-law Mary Miller remembered this style well. “He always used his tripod, so he was not looking at people through a camera. He was having a conversation,” she said.

Thinking about Miller’s prodigious catalog, Mary noted, “He loved those Paris pictures, which were wonderful, but I think his Vermont pictures were among his best.” She added, “Just these old Vermonters, doing things their way and appreciating their way of life…definitely his best.”

“Color distracts,” Mary recalled her brother-in-law saying. Most of Miller’s ski photographs were shot in color, but not the photographs of Vermonters. “Those were in black and white so you could see their stories,” she said. The training he received at Life magazine as a writer helped Miller develop an overall style that was free of distraction.

Fellow journalists and photographers also recognized there was something special in Miller’s work, garnering him a long list of awards and accolades, including a Lifetime Achievement in Journalism award from the International Association of Ski History in 1994; Book of the Year for Vermont Farm Women from Vermont Book Professionals Association, Publishers Marketing Association, and Independent Publisher magazine in 2003; the 2014 Gold Award from the New England Book Festival for A Lifetime of Vermont People; and the Paul Robbins Journalism award by the Vermont Ski & Snowboard Museum in 2017.

The New Year’s Day 2006 editorial page of The Burlington Free Press announces Peter Miller as Vermonter of the Year. Click to enlarge.

The Burlington Free Press and Vermont State Legislature in 2006 named Miller Vermonter of the Year. The honor was recorded in an editorial by the newspaper and in a joint resolution adopted by the Vermont Legislature. It recognized Miller’s career achievements, in particular how his work “preserved a record of Vermont’s cultural landscape for future generations.”

In 2016, the weekly Waterbury Record newspaper published the results of a reader survey that declared Miller “Mr. Waterbury.” Miller wrote in a blog post that he would decline the honor, as he preferred to be known as “the mayor of Colbyville.”

In 2013, Patrick Leahy, then a U.S. Senator and himself an amateur photographer, gave a speech on the Senate floor celebrating Miller’s “unique ability to capture the Vermont spirit…and his [unparalleled] consistent approach to producing authentic depictions of the Vermont way of life.” The Senate unanimously consented to include a VTDigger news article about Miller written by Vermont journalist Andrew Nemethy in the Congressional Record.

Peter Miller at the University of Toronto in 1952 receives a trophy from Professor K.B. Jackson. From the archive of the university's Hart House Camera Club

Today, a new generation of media makers and documentarians is learning to appreciate Miller’s work. Jesse McDougall, of Waterbury Center, visited Miller a few times in the last couple of years to talk about his craft and Miller’s alma mater, the University of Toronto, where McDougall is currently a senior double-majoring in politics and Spanish. McDougall is also the host of the podcast, Tracks from Abroad, and produces documentary shorts on his YouTube channel.

“I think he remembered those days [at University of Toronto] fondly because he met [Yousuf] Karsh on our campus, whose work would shape the rest of his life and inspire Peter's photographic eye,” McDougall wrote in an email.

McDougall reflected that “Reading his work reminded me that Vermont wasn't always like this. I realized that a single-chair chairlift was once considered groundbreaking tech, that some folks used to get the bulk of their calories from hunting and fishing, and that in the 1960s Waterbury was once a 'ghost town,' as he [Miller] described it.”

Peter Miller on assignment on Stowe Street during Not Quite Independence Day in Waterbury. Photo by Gordon Miller

While at University of Toronto, Miller was a member of the Hart House Camera Club, which still displays copies of the photos for which he won awards in the 1950s. Inspired, McDougall organized a virtual event in September 2021, hosted by the camera club, where Miller presented a collection of his photographs and reflected on some of what he had learned since graduation. “He had many colorful descriptions of his images and the context in which he took them. People liked to hear it all,” McDougall said.

Like the subjects he photographed, Miller’s own story is contoured and nuanced with many shades of gray. Publicly known for his photography and his unabashed criticisms of the increased cost of living in his beloved state, Miller was also attentive to the intricate workings of other media, especially food. Sometimes he shared his musings like in this first-person account of executing construction of an apple pie using fruit picked from his backyard trees.

McDougall recalled a story Miller once told him about buying an ice cream machine as a diversion from a deep bout of depression. “He became entranced with the different ingredients, their temperatures, the milk and sugar and so on that affected the final product. According to him, that ice cream maker played a key role in getting him through a rough time,” McDougall explained.

Longtime friend Anne Imhoff first met Miller in 1977 when she rented the downstairs apartment of his house on Route 100. Imhoff had come to Vermont from Massachusetts to “see if I could stand living here,” she explained. A friend had originally rented the apartment and Imhoff moved in with her, eventually getting the place to herself.

“Peter really loved to ski, and he loved to hunt with his dog, Parker,” Imhoff recalled. Although she is a devoted fan of Miller’s photography, Imhoff’s memories of time shared with him focus largely on his “very good taste” in food and wine.

“I loved it when he was going to cook dinner,” Imhoff recalled of the times she was invited up to eat. “He was a wonderful cook, closer to being a chef. We had woodcock and French green beans with almonds. I had never thought about putting almonds in vegetables!” she laughed.

In Waterbury Center, October 12, 2019. Photo by Gordon Miller

Another time, the two friends hiked Camel’s Hump and enjoyed “a French picnic, with wine and cheese and baguettes,” said Imhoff. Like in his photographs, “you can see his sense of delicacy in a composition,” she added.

Mary Miller’s most cherished memory also involves food. For his 89th birthday on January 6 of this year, Mary took her brother-in-law out to lunch in Stowe. “We had the best time. That’s the moment I will remember him for,” she said.

For Peter Miller himself, life was about experiencing a story, not just telling it. He closed his last Front Porch Forum posting on February 20, 2023, in which he asked for help curating his vast archive, with an admission: “To me, photography is a calling, a part of my soul. I follow the Navajo path with their prayer, I Walk in Beauty. I search for beauty in a face and the way light illuminates Vermont hills and valleys and me, too.”

Bridgeside Books in downtown Waterbury has partnered with Miller’s estate to sell the remaining books in Silver Print Press’s stock, starting Friday, April 28. Owner Katya d’Angelo says they would have limited editions of ‘A Lifetime of Vermont People,’ both hardcover and paperback copies of ‘Nothing Ever Happens in Colbyville, Vermont,’ and paperback copies of ‘Vanishing Vermonters.’

Additionally, Mary Miller confirmed that the family is planning both a memorial service and an obituary, with more details to come.

Waterbury Center resident Cheryl Casey is a professor of communication at Champlain College and president of the Waterbury Historical Society. Lisa Scagliotti contributed research to this article.