A boxelder for Terry

November 22, 2024 | By Elise Tillinghast | The Outside StoryIllustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol

My friend Terry Gulick, who passed away earlier this year, used to tease me about my favorite yard tree. Terry did a lot of gardening jobs when he wasn’t mentoring kids and he was amused and a little offended by what I’d allowed to grow up in my former vegetable patch. It was bad enough that I was letting a tree take over prime soil, but did it have to be a boxelder?

“It’s a trash tree,” he told me, shaking his head.

Boxelder (Acer negundo) – also known as ash-leaf maple, elf maple, Manitoba maple, and other, less printable names – is the misfit cousin of the Acer family. It’s the only maple species that won’t sprout in shade, and you’re more likely to find specimens growing in a scraggly line along a road or riverbank than deep in a forest. It’s also the only maple that’s dioecious, meaning that every tree produces exclusively male or female flowers. Its leaflets look like nothing you’d find on the side of a syrup bottle or – despite the tree’s alternative name – on an ash tree. They’re toothy, with a strong resemblance to poison ivy leaves.

Unlike the stately sugar maple, which can endure for more than four centuries, the boxelder’s typical lifespan, from seed through senescence, is on a human scale. A 75-year-old boxelder is already an old tree. It grows quickly – in good soils, more than 2 feet each year – and this trait, along with its toughness, has made boxelder a popular choice for erosion control and windbreak plantings.

“Trash” seems a harsh epithet for a tree, but the species surely inspires a lot of trash talk. One reason is the low value of boxelder wood. On the plus side, carvers appreciate its softness and its occasional pink-to-red staining. However, the wood is too weak to be useful for most construction and manufacturing purposes. It’s also low density, which makes it a poor choice for firewood beyond kindling.

The most intense criticisms of boxelder come from people such as Terry who have spent hours cleaning up after it. A U.S. Forest Service profile of the species notes its reputation as a “dirty tree” and if you skim through field books, you’ll find numerous disparaging references to the species’ vulnerability to rot, its complicity as a host of home-invading boxelder bugs, its tendency to scatter wind-snapped twigs, and the way it spread seeds with bunny-like abandon.

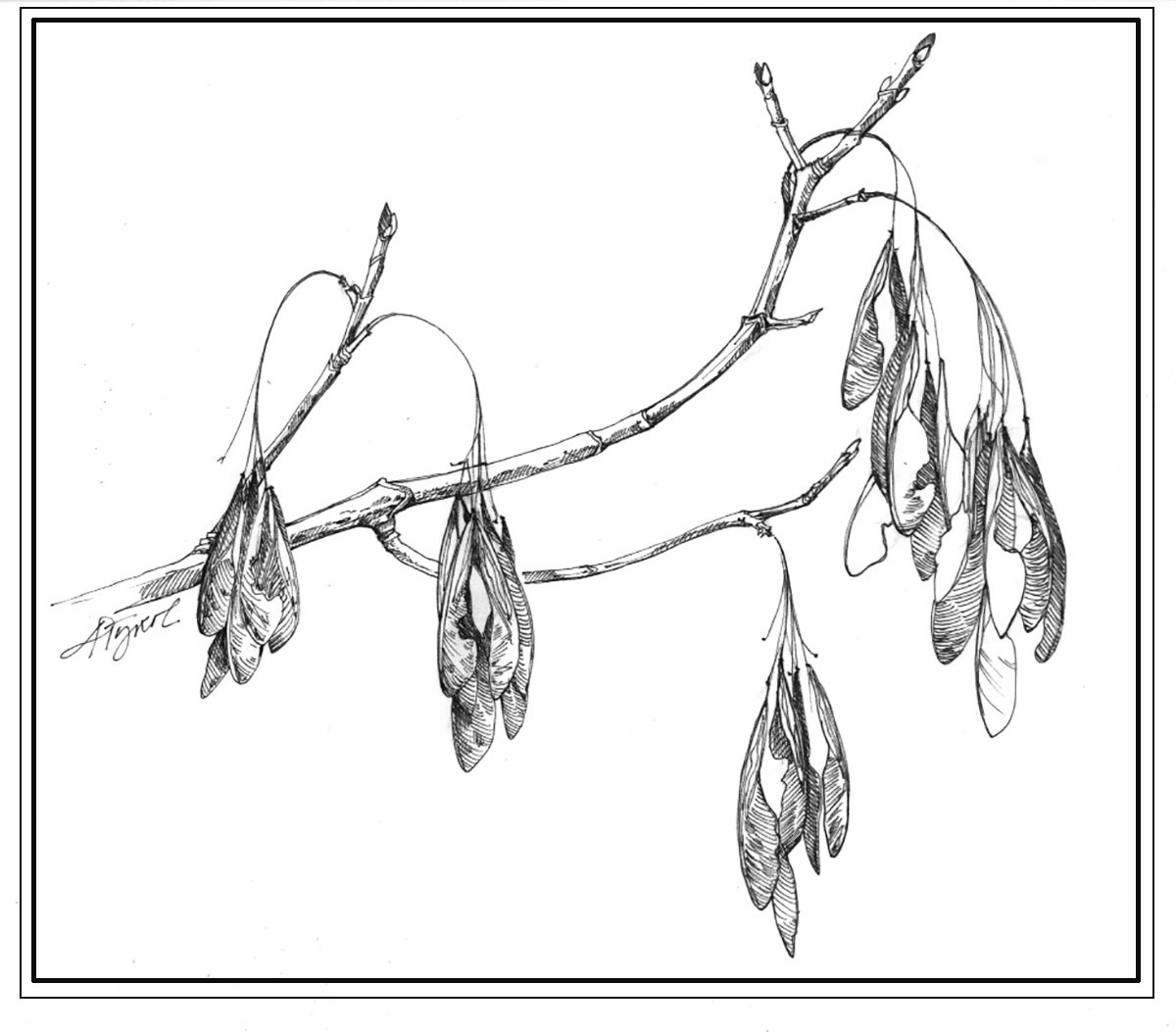

For Terry, boxelder’s voluminous seed production was its greatest sin. Sure enough, just as he warned me would happen, my female tree was already bearing seeds by its eighth year, and every autumn since has produced a bigger crop. As I write this, there are thousands upon thousands of samaras dangling in clusters. I think they’re pretty. And birds love them.

Because many of the samaras linger on their stems late into winter, they offer an easily accessible food for year-round resident birds and for cold weather visitors that fly down from Canada. For instance, the evening grosbeak, which breeds in Canada and has been in steep population decline, is partial to boxelder seeds. If for no other reason than to help this threatened bird, the tree deserves space in my yard.

There are other, personal reasons I have for loving this tree. The boxelder appeared in my daughter’s first year, soon after I gave up the garden. And it has grown vigorously, just as she and her younger brother have, the pencil marks on the kitchen door tracking their rising heights. The boxelder’s forked trunk, which split into a trident 2 feet off the ground, formed just the right holds for small hands and feet.

Terry was good to my kids, and to other people’s kids who needed him more. He taught children who had a lot of sadness in their lives how to pitch tents, climb trees, and roast s’mores on the fire. When I asked about these experiences, he’d deflect and ask how I could sleep at night, knowing that was growing in my yard.

But the joke’s on him. When I look at my crooked, scrappy tree, its samaras metallic in the low November light, I hear Terry’s voice and remember his kindness.

Elise Tillinghast is the past executive director and editor of the Center for Northern Woodlands Education and is currently editor-at-large for Nature and the Environment at Brandeis University Press. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.