Horned larks enliven sleeping fields

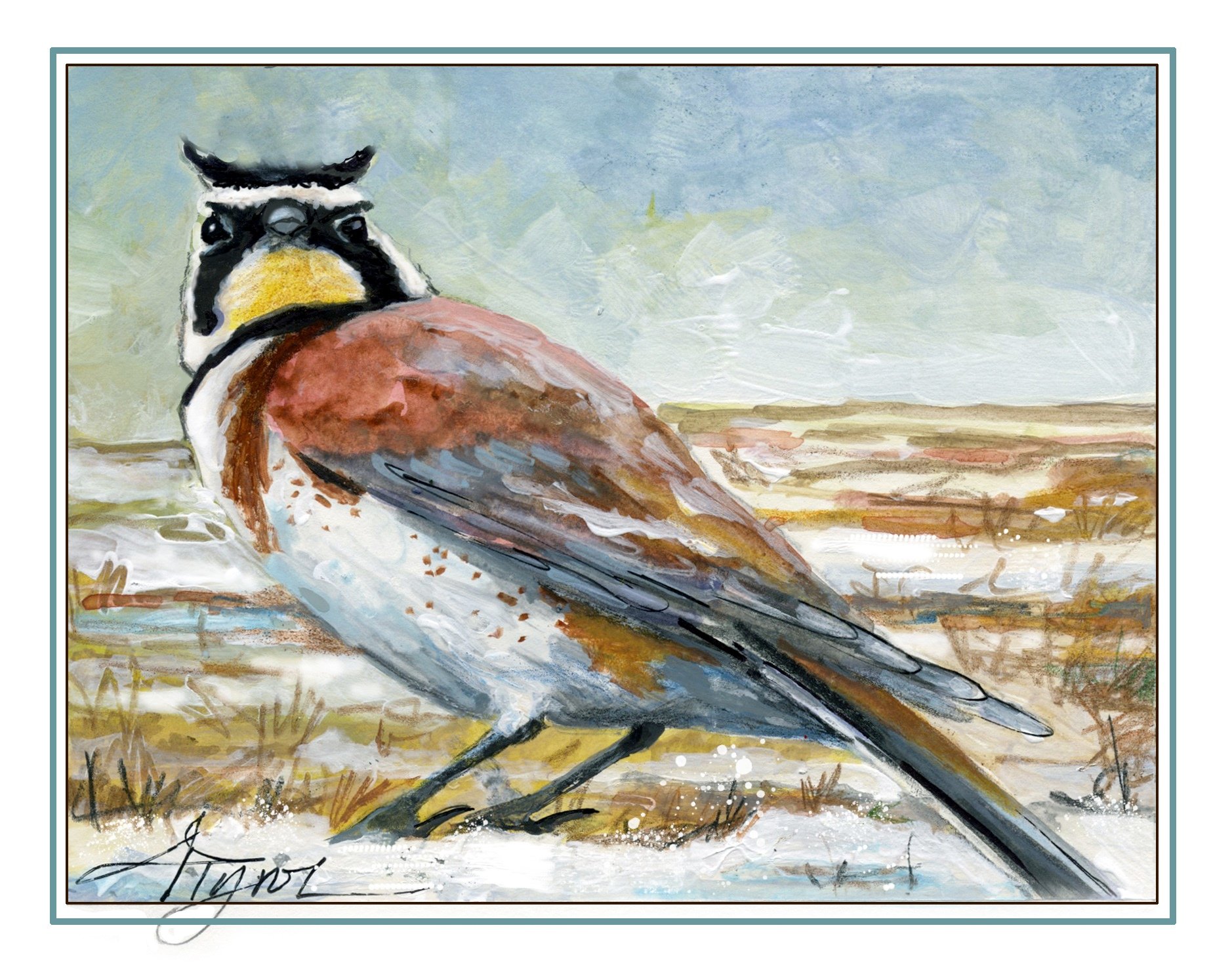

December 23, 2024 | By Colby Galliher | The Outside StoryIllustration by Adelaide Murphy Tyrol

Halloween is long past, but you may notice devilish figures hanging out in scrubby fields and open areas this winter: horned larks.

These birds are North America’s only true lark species. They reside year-round in parts of the Northeast, such as Vermont’s Champlain Valley, but disperse across the region more widely in winter, when the stark landscape makes them easier to spy.

Horned larks (Eremophila alpestris) are so named for tufts of delicate black feathers along the sides of the male bird’s head. Males can raise these diminutive “horns” at will, likely as part of courtship. But even when perked, these adornments are small enough that they may be difficult to distinguish from afar.

Though their horns, when visible, are a telltale identification method, spotting horned larks can still be a challenge. In the winter, they flock with other species, including dark-eyed juncos, snow buntings, and Lapland longspurs, meaning birdwatchers often must discern them from the rest of the crowd. With their tawny plumage of brown and beige, horned larks often blend in with the fields where they forage for seeds and waste grain. These small birds are more likely to catch your eye when they alight on snowpack, their black eye masks and horns bold against a forehead and throat of warm yellow.

Horned larks’ habitat preferences span natural and human-disturbed environments. They need open, sparsely vegetated areas where they can forage in winter and nest in summer. Though they can live in areas of greatly varying altitude, from deserts and Arctic tundra far below sea level to alpine zones, they tend to “avoid places where grasses grow more than a couple of inches high,” according to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s profile of the species. In winter in northern New England, these birds are often in fields or in large flat areas, such as airstrips.

Undeterred by cold and snow, horned larks begin breeding as early as February. Males perform a swooping flight display to demarcate and defend their territories, embellishing their acrobatics with a tinkling song. A female constructs a nest by digging a depression in bare ground or utilizing a preexisting one, adding a stoop made of dirt clods, stones, and husks. The first brood is generally out of the nest by May, and the parents may raise two additional broods through the remainder of the breeding season.

Though the horned lark is a prodigious breeder and remains a common species, surveys indicate a rapid population decline in recent decades. The avian conservation group Partners in Flight lists horned larks as a “Common Bird in Steep Decline” and the North American Breeding Bird Survey has found a population decrease of almost 65% in the past half-century or so.

The reasons for this decline are multifaceted, mirroring challenges other grassland birds face. A major culprit is habitat conversion. The large-scale deforestation that accompanied European settlement centuries ago allowed the horned lark and other grassland birds to spread east from their traditional range in the American prairie into newly created croplands and pastures in the Northeast.

As agriculture shifted west during the mid-19th century, and many of the Northeast’s farms were abandoned, untended fields began reverting to forest. While this trend has benefitted forest-loving birds and wildlife species, it has reduced the amount of habitat available to the horned lark and other grassland birds. Today, these remaining open spaces are prime targets for development.

Other land-use changes have also harmed horned lark populations. Earlier mowing of fields destroys nests and can kill chicks as well as adult birds, while heavy pesticide applications can diminish populations by eliminating their insect prey or killing birds via direct exposure. The bright side is that species-specific conservation projects aimed at preserving the Northeast’s remaining grasslands, such as the Bobolink Project, are likely to benefit the horned lark by preserving both the breeding and non-breeding habitat the species needs.

When you’re out on your snowshoes or cross-country skis this winter and longing for spring migration, study bare patches in the sleeping fields you pass. You may spot a horned lark shuffling along, adding a bit of color and personality to the short, drab days of winter.

Colby Galliher is a writer who calls the woods, meadows, and rivers of New England home. The Outside Story is assigned and edited by Northern Woodlands magazine and sponsored by the Wellborn Ecology Fund of New Hampshire Charitable Foundation.