Waterbury retailers and restaurants eggs-asperated by egg supplies and pricing

February 20, 2025 | By Sandy Yusen | Correspondent In Waterbury, the question isn’t which came first, the chicken or the egg? It’s more like are there any eggs today?

Restocking the egg case at Shaw’s. Photo by Sandy Yusen

Last week, the Roundabout heard from readers about the scarcity of eggs as a photo of the egg section at Shaw’s with shockingly barren shelves made the rounds on social media. We set out to crack the case, and found that the real picture of Waterbury’s egg supply is a bit scrambled depending on where and when you shop.

The good news is that there are usually plenty of eggs to be found in local establishments. The not-so-good news: Shoppers can expect to shell out more money for their eggs, at least in the near future.

Waterbury is by no means alone in facing this crisis. National headlines are rife with reports of an egg shortage driven by an outbreak of avian influenza (or bird flu), which has decimated the egg-laying hen population on farms across the country. The result has been a sharp spike in the price of eggs. Last week, the U.S. Labor Department reported that the price of eggs rose 15.2% over the past month, and 53% over the last year. Nationally, the average price of a dozen grade A eggs hit a record high of $4.95 in January – more than double the low of $2.04 recorded in August 2023.

Thankfully, fears of no eggs at Shaw’s turned out to be eggs-aggerated. A recent visit found the store’s resident egg man unpacking crates and restocking shelves. “I have so many eggs I don’t even know where to put them all,” he said. Shaw’s egg prices clock in at just slightly higher than the national average. Prices start at $4.99 for a dozen large grade A eggs, and higher for other organic and pasture-raised varieties.

Egg supplies are running out before restocking can happen. The egg case at Shaw’s is nearly cleaned out last week before a new supply arrived. Photo by Laurel Scannell

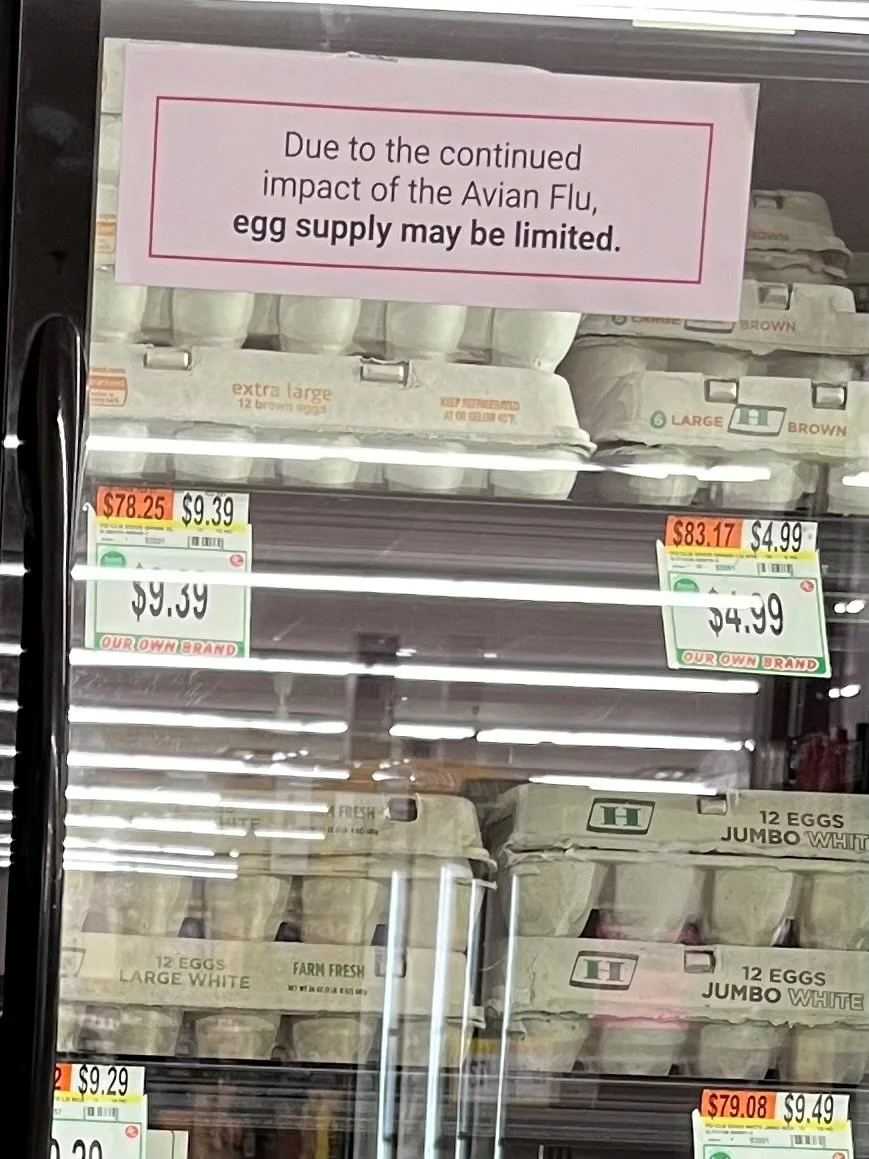

Downtown at the Village Market of Waterbury, staffers say they have been fielding calls about whether they have eggs, and customers have been buying up eggs as quickly as they can be restocked. Signage on the refrigerator case warns: “Due to the continued impact of the Avian Flu, egg supply may be limited.” Prices range from $5.49 for a dozen large eggs to $9.29 for some varieties.

The high demand for eggs has created a crunch for the region’s smaller grocers in particular. At Woodstock Farmers’ Market in Waterbury Center, store Manager Mark Alperin admits, “It’s been bad.” Woodstock’s purchasers have been beaten to the punch by larger grocers who buy out local egg vendors when they can’t get adequate quantities through their regular, larger distributors.

Normally, Alperin estimates Woodstock goes through eight cases per week of 15 dozen eggs each. But not recently. “We’re getting in maybe half of that and they’re selling basically immediately,” he said.

Recently, Alperin explained, Woodstock’s suppliers have provided eggs in “kitchen bulk” shipments, forcing Alperin’s team to buy egg cartons from Amazon and package them themselves. “We literally can’t get eggs any other way,” he says. They’ve posted signs promising customers that the eggs were local despite the unfamiliar packaging.

Woodstock has had to raise prices to cover its margins on the higher-priced eggs – to $11.99 for a dozen. “We’re doing what we can to make it accessible, but we can’t sell things at a loss either,” Alperin said, adding that for the store’s baked goods and prepared foods such as quiches, the cost of ingredients is easier to absorb without raising prices for now.

“We try to be the best we can at being full-service – anyone can get whatever they need here – but right now we just can’t keep up with the eggs,” Alperin said. He knows Woodstock customers prefer to buy products sourced locally. “When you buy local and you buy organic, small batch you can lose consistency. Sometimes it results in nothing being available.” Still, he encourages customers to come and shop, joking, “Buy anything but eggs.”

Message in the egg case at the Waterbury Village Market. Photo by Sandy Yusen

Egg-flation has also been a hot topic at The Roots Farm Market in Middlesex. Store manager Martha Coe says that for the most part, customers have been understanding. “The majority of people that come through here, I think very much know what’s going on with regard to why this is happening,” she said. But, “at the end of the day, the price of eggs is going up and people are not happy with that.”

Roots has been able to secure enough eggs to meet customer needs, which Coe attributes to the store’s longstanding relationships with small regional farms. Hen flocks on these farms have remained healthy, although hens’ production is affected by seasonality, Coe said. “They’re slowing up for the season. It’s dark and it’s cold and the chickens aren’t really laying.”

Coe speculates that the slower egg production and increased price in chicken feed on top of existing market forces have caused egg prices to spike dramatically. Roots store buyer Francis Harrison says that just over the last week, “I had to jump everything up by two whole dollars extra for a dozen. At the time it was already approaching $10, and in order to make any kind of a profit, we had to bring it up close to 12.”

Harrison explained further: “We’re not trying to pull a fast one or anything. We’re kind of at the mercy of what’s going on and all the different factors and we appreciate our customers who can stand with us through that.”

When food supplies are tight at grocery stores, it also affects the Waterbury Common Market, the food shelf that provides free food assistance to Waterbury area residents. Director Sara Whitehair explains that eggs are an easy and nutritional source of protein, and until recently, relatively inexpensive.

In recent months, however, the market has struggled to sustain its egg supply because of high prices as well as limits on egg purchases at stores like Costco. She said she hopes to keep up with demand. “We have always considered eggs to be an essential item at the Common Market and we try to always have them available for our shoppers,” she said.

Waterbury restaurants eggs-ercise patience

Grocers aren’t the only ones feeling the pinch on eggs – local restaurants have been impacted as well.

Park Row Cafe has been able to sustain its egg supply to support its menu, according to manager Brittany Murray. “The biggest problem is we do breakfast all day long, all seven days a week, so we kind of have to have eggs,” she said.

Over the last two weeks, however, Murray reports that eggs have tripled in price. “We get a case of eggs usually for about $60, and I think right now it’s about $180 for a case of eggs,” she said.

Despite this increase, Park Row hasn’t passed on any pricing surcharges to customers. “We don’t do that,” Murray explained. “We’re probably the cheapest place in town as well. It costs us a little extra. Our regulars still come in every day, so we do what we can for them and they do what they can for us.”

Murray shares that some customers have changed their order, avoiding eggs due to fear of bird flu, despite assurances by Vermont Commissioner of Health Dr. Mark Levine that the risk to the public remains low. “A lady asked me if I could make a breakfast burrito with no eggs,” Murray said with a laugh.

But Murray, who has persevered through other food shortages over the years, said she isn’t worried. “We just kind of wait it out,” she said, adding that the restaurant wants customers to know, “We got eggs, come and get ’em!”

Local breakfast spots like Stowe Street Cafe use many eggs to prepare popular menu items like this egg, cheese and sausage sandwich. Courtesy photo

At Stowe Street Cafe, owner Nicole Grenier reports that the cafe’s supplies have not been interrupted, but admitted, “We’re kind of walking on eggshells about it.”

“We've absolutely incurred steady price increases of several more dollars per case every week for the past six weeks or so,” she recounted. The cafe’s chefs are keeping a close eye on market trends but don’t plan to change pricing or menu items for now. “Breakfast sandwiches and burritos, and our recently expanded all-day brunch menu on Saturdays and Sundays are extremely popular, so we’re doing everything we can to continue providing what our customers love,” Grenier said.

Other local restaurants are taking the same wait-and-see approach. Maxi’s, which also serves breakfast all day, has not increased prices or up-charged for eggs. Gallus Handcrafted Pasta, which incorporates eggs into its fresh pastas, continues to sustain its supply while absorbing recent price increases.

Going to the source of the egg supply chain

One of the egg suppliers to regional restaurants, small local grocers, and individuals in the area (including Waterbury) for delivery or pick-up at its farm store is Maple Wind Farm in Richmond. Marketing director James Oakley says the farm has experienced a jump in demand as a result of egg shortages among larger distributors. Because the farm’s primary goal is to service its direct customers, they aren’t always able to meet the increased demand from wholesale, food service, and retail customers. “We’re basically maxed out, so whatever we can produce gets bought,” he said.

Oakley reports that the farm’s egg production has not been affected by bird flu, thanks to precautions such as staffers dipping their boots into a solution that prevents the spread of potentially nefarious germs before entering the barn.

Maple Wind sells its pasture-raised eggs for $7.90 per dozen, and it doesn’t plan to react to market changes by raising prices. “We just wouldn't feel good about doing that,” Oakley said. A recent email from the farm to customers described its pricing philosophy: “We price our eggs based on what it actually costs to raise them – not on what the market says they’re ‘worth’ this week.”

The farm is currently running a promotion where customers can get a dozen eggs free if they spend $60 at the farm’s market in Richmond or online. “Full transparency – we are kind of playing the moment a little bit with that promotion, but we have to take what we can get to keep our farm going,” Oakley admitted.

Is there a sunny side up?

When will the egg supply be replenished, allowing prices to come down or at least stabilize? For answers, the Roundabout consulted an eggs-pert in the field: Dr. Ricky Volpe, professor of agribusiness at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo, California, and former economist at the USDA Economic Research Service in Washington, D.C.

Volpe’s outlook is a mixed bag. “I don’t think we need to worry about any sort of long-term egg shortages, but I do think that higher egg prices in 2025 are almost a foregone conclusion,” Volpe said. “Right now, USDA is saying that they’re probably going to increase by another 20 or 30% this year. So we’re certainly not looking at any relief.”

Volpe explained that the avian flu has been a shock to the supply chain, driving up egg prices dramatically over the past two years. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, nearly 159 million commercial birds have been lost to avian influenza since the outbreak began in 2022. “That’s creating substantial supply chain interruptions and the cost of replenishing those inventories, especially in a relative expedited time frame, is very expensive,” he said.

That’s because of the time lag of six to eight weeks for egg-laying hens to become market-ready and productive, Volpe said. “The best estimate I’ve heard is that if avian flu really pulls back, we should start seeing some price relief in April or May. But that’s the best-case scenario.”

And that’s if the avian flu ebbs. Volpe warns: “We know it’s transmissible. We know it’s dangerous. And we’re kind of all just hoping it goes away.”

The good news is that Vermont may be better positioned to weather this crisis, because local grocers tend to have connections with small, local farms to supplement the egg supply, rather than relying solely on larger commercial egg laying facilities with conditions that make them more susceptible to the avian flu. “Any place that is able to source locally in good times or bad and meet demand consistently doing so has a leg up,” Volpe noted.

Something else consumers should keep in mind, Volpe says, is that although eggs are currently in the spotlight, they are actually an outlier in terms of increased food prices. “Most food categories are on track for below-average food price inflation in 2025, and that’s really, really good news,” he said. “No one’s saying that food prices are not high, but they’re also not really increasing, at least not nationwide. They’ve been mostly flat for a while and they’re projected to stay that way.”

While shoppers wait for the egg prices to stabilize, they may be putting fewer eggs in their baskets. Some retailers have instituted purchasing limits on eggs, to prevent the kind of stockpiling that happened with toilet paper during the COVID-19 pandemic. Volpe explains the rationale behind the rationing: “Eggs are hot right now. And they have been for years.”

He cites the dietary guidance for Americans swinging back to recommending eggs as a versatile source of lean protein. “We love our eggs. And that’s not changing,” he said. “No matter what happens to the price of eggs, they keep flying off the shelves.”